what appear to be the characteristics of effective teams in public health settings?

13.1 Understanding Small Groups

Learning Objectives

- Define small group communication.

- Discuss the characteristics of pocket-size groups.

- Explain the functions of small groups.

- Compare and contrast unlike types of small-scale groups.

- Discuss advantages and disadvantages of small groups.

Most of the communication skills discussed in this volume are directed toward dyadic communication, meaning that they are applied in two-person interactions. While many of these skills can be transferred to and used in small-scale group contexts, the more circuitous nature of group interaction necessitates some adaptation and some additional skills. Small group advice refers to interactions among iii or more people who are connected through a common purpose, mutual influence, and a shared identity. In this section, we volition learn near the characteristics, functions, and types of small groups.

Characteristics of Small Groups

Dissimilar groups have dissimilar characteristics, serve different purposes, and can lead to positive, neutral, or negative experiences. While our interpersonal relationships primarily focus on relationship building, modest groups commonly focus on some sort of job completion or goal accomplishment. A higher learning community focused on math and science, a campaign squad for a state senator, and a group of local organic farmers are examples of small groups that would all have a different size, structure, identity, and interaction pattern.

Size of Small Groups

There is no set up number of members for the ideal modest group. A small group requires a minimum of three people (because two people would be a pair or dyad), but the upper range of group size is contingent on the purpose of the group. When groups abound across fifteen to xx members, it becomes difficult to consider them a small group based on the previous definition. An assay of the number of unique connections between members of small-scale groups shows that they are deceptively circuitous. For case, inside a half-dozen-person group, there are fifteen separate potential dyadic connections, and a twelve-person group would have sixty-half dozen potential dyadic connections (Hargie, 2011). Every bit yous can see, when we double the number of group members, we more than than double the number of connections, which shows that network connection points in pocket-sized groups grow exponentially as membership increases. So, while there is no fix upper limit on the number of group members, information technology makes sense that the number of group members should be limited to those necessary to reach the goal or serve the purpose of the group. Small groups that add too many members increase the potential for grouping members to feel overwhelmed or disconnected.

Structure of Small Groups

Internal and external influences touch a grouping'due south construction. In terms of internal influences, fellow member characteristics play a role in initial grouping formation. For instance, a person who is well informed about the group's task and/or highly motivated equally a group member may sally equally a leader and prepare into motion internal decision-making processes, such equally recruiting new members or assigning group roles, that affect the construction of a group (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). Different members will also gravitate toward different roles within the group and will advocate for sure procedures and courses of activity over others. External factors such as group size, task, and resources also affect grouping construction. Some groups will accept more command over these external factors through decision making than others. For instance, a commission that is put together by a legislative body to look into ethical violations in athletic organizations will probable accept less control over its external factors than a self-created weekly volume club.

A self-formed study group likely has a more flexible structure than a metropolis council committee.

William Rotza – Group – CC Past-NC-ND 2.0.

Group structure is also formed through formal and breezy network connections. In terms of formal networks, groups may take clearly defined roles and responsibilities or a hierarchy that shows how members are connected. The group itself may also be a part of an organizational hierarchy that networks the group into a larger organizational construction. This type of formal network is particularly important in groups that have to study to external stakeholders. These external stakeholders may influence the group's formal network, leaving the group little or no control over its construction. Conversely, groups accept more command over their breezy networks, which are connections amid individuals within the group and among grouping members and people outside of the group that aren't official. For example, a group member's friend or relative may be able to secure a space to agree a fundraiser at a discounted rate, which helps the grouping attain its task. Both types of networks are important considering they may help facilitate data exchange within a group and extend a grouping's achieve in order to access other resources.

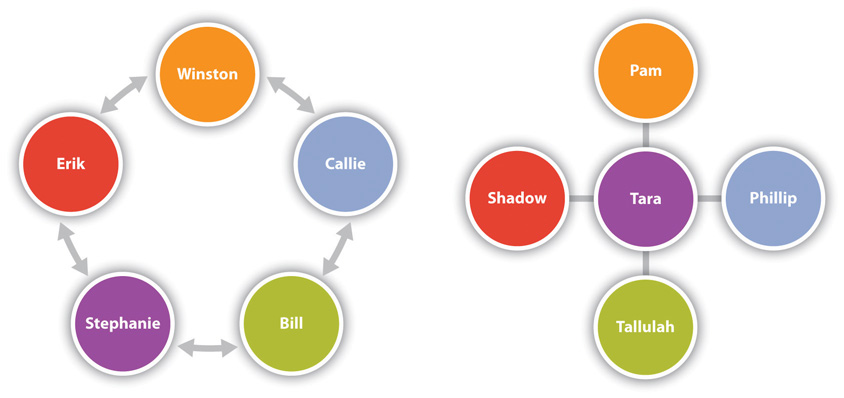

Size and structure likewise affect communication within a group (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). In terms of size, the more people in a group, the more problems with scheduling and coordination of communication. Remember that time is an important resources in most group interactions and a resources that is usually strained. Structure can increment or subtract the flow of advice. Reachability refers to the way in which one fellow member is or isn't connected to other group members. For example, the "Circumvolve" group structure in Effigy thirteen.1 "Modest Group Structures" shows that each group member is connected to two other members. This can make coordination easy when merely 1 or two people need to be brought in for a determination. In this example, Erik and Callie are very reachable by Winston, who could easily coordinate with them. However, if Winston needed to coordinate with Beak or Stephanie, he would have to wait on Erik or Callie to reach that person, which could create delays. The circle tin be a good structure for groups who are passing forth a chore and in which each member is expected to progressively build on the others' work. A grouping of scholars coauthoring a research paper may piece of work in such a mode, with each person calculation to the newspaper so passing information technology on to the next person in the circumvolve. In this case, they can ask the previous person questions and write with the next person's area of expertise in mind. The "Wheel" group structure in Effigy 13.1 "Pocket-size Group Structures" shows an alternative organization pattern. In this structure, Tara is very reachable by all members of the group. This can exist a useful construction when Tara is the person with the virtually expertise in the task or the leader who needs to review and approve piece of work at each footstep earlier it is passed forth to other grouping members. Only Phillip and Shadow, for example, wouldn't likely piece of work together without Tara existence involved.

Figure 13.1 Pocket-sized Grouping Structures

Looking at the group structures, we tin can make some assumptions about the communication that takes identify in them. The wheel is an example of a centralized construction, while the circumvolve is decentralized. Research has shown that centralized groups are improve than decentralized groups in terms of speed and efficiency (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). Simply decentralized groups are more constructive at solving complex problems. In centralized groups like the bicycle, the person with the nigh connections, person C, is besides more likely to exist the leader of the group or at least have more than condition among grouping members, largely because that person has a broad perspective of what'southward going on in the group. The most central person can also human activity as a gatekeeper. Since this person has access to the most information, which is usually a sign of leadership or status, he or she could consciously decide to limit the menstruation of data. Merely in complex tasks, that person could get overwhelmed past the burden of processing and sharing information with all the other grouping members. The circle structure is more likely to emerge in groups where collaboration is the goal and a specific task and course of action isn't required under time constraints. While the person who initiated the group or has the near expertise in regards to the task may emerge as a leader in a decentralized grouping, the equal access to information lessens the hierarchy and potential for gatekeeping that is present in the more centralized groups.

Interdependence

Small groups showroom interdependence, meaning they share a common purpose and a common fate. If the actions of one or ii grouping members atomic number 82 to a group deviating from or not achieving their purpose, so all members of the group are affected. Conversely, if the actions of only a few of the group members pb to success, then all members of the group benefit. This is a major contributor to many college students' dislike of group assignments, because they feel a loss of command and independence that they take when they complete an assignment alone. This business organization is valid in that their grades might suffer because of the negative deportment of someone else or their hard work may go to benefit the group member who just skated by. Group coming together omnipresence is a clear example of the interdependent nature of group interaction. Many of us have arrived at a group meeting simply to observe one-half of the members present. In some cases, the group members who show up have to leave and reschedule because they tin can't accomplish their task without the other members nowadays. Group members who attend meetings but withdraw or don't participate can also derail group progress. Although it can be frustrating to have your chore, course, or reputation partially dependent on the deportment of others, the interdependent nature of groups can also lead to higher-quality performance and output, specially when grouping members are accountable for their actions.

Shared Identity

The shared identity of a grouping manifests in several means. Groups may have official charters or mission and vision statements that lay out the identity of a group. For example, the Girl Scout mission states that "Daughter Scouting builds girls of backbone, conviction, and character, who make the earth a amend identify" (Daughter Scouts, 2012). The mission for this big organisation influences the identities of the thousands of small groups chosen troops. Group identity is often formed around a shared goal and/or previous accomplishments, which adds dynamism to the group as information technology looks toward the future and back on the past to inform its present. Shared identity can also be exhibited through group names, slogans, songs, handshakes, clothing, or other symbols. At a family reunion, for example, matching t-shirts specially fabricated for the occasion, dishes fabricated from recipes passed down from generation to generation, and shared stories of family members that accept passed away assistance found a shared identity and social reality.

A cardinal element of the formation of a shared identity within a group is the establishment of the in-grouping as opposed to the out-group. The degree to which members share in the in-group identity varies from person to person and grouping to group. Fifty-fifty within a family, some members may not nourish a reunion or become as excited about the matching t-shirts equally others. Shared identity also emerges as groups become cohesive, meaning they place with and like the group's task and other grouping members. The presence of cohesion and a shared identity leads to a edifice of trust, which tin can as well positively influence productivity and members' satisfaction.

Functions of Modest Groups

Why do we join groups? Even with the challenges of grouping membership that we accept all faced, we still seek out and want to be a office of numerous groups. In some cases, we join a group because nosotros demand a service or access to data. Nosotros may also be drawn to a group because we admire the group or its members. Whether we are witting of it or not, our identities and self-concepts are built on the groups with which nosotros identify. So, to answer the earlier question, we join groups considering they function to assistance the states meet instrumental, interpersonal, and identity needs.

Groups See Instrumental Needs

Groups have long served the instrumental needs of humans, helping with the most basic elements of survival since ancient humans beginning evolved. Groups helped humans survive by providing security and protection through increased numbers and access to resource. Today, groups are rarely such a matter of life and death, but they still serve of import instrumental functions. Labor unions, for example, pool efforts and resources to attain material security in the form of pay increases and health benefits for their members, which protects them by providing a stable and undecayed livelihood. Individual group members must also work to secure the instrumental needs of the group, creating a reciprocal relationship. Members of labor unions pay dues that aid support the grouping's efforts. Some groups also come across our advisory needs. Although they may not provide fabric resource, they enrich our knowledge or provide data that we can apply to then run into our own instrumental needs. Many groups provide referrals to resources or offering communication. For instance, several consumer protection and advancement groups have been formed to offering referrals for people who accept been the victim of fraudulent business practices. Whether a group forms to provide services to members that they couldn't go otherwise, advocate for changes that will affect members' lives, or provide information, many groups encounter some type of instrumental need.

Groups Meet Interpersonal Needs

Group membership meets interpersonal needs past giving us access to inclusion, control, and support. In terms of inclusion, people have a fundamental drive to be a role of a group and to create and maintain social bonds. As we've learned, humans have ever lived and worked in small groups. Family and friendship groups, shared-interest groups, and activity groups all provide u.s. with a sense of belonging and being included in an in-grouping. People also bring together groups because they want to have some control over a decision-making procedure or to influence the outcome of a group. Being a part of a group allows people to share opinions and influence others. Conversely, some people bring together a group to be controlled, because they don't want to be the sole decision maker or leader and instead want to be given a role to follow.

Just every bit we enter into interpersonal relationships because we like someone, we are drawn toward a group when we are attracted to it and/or its members. Groups also provide support for others in ways that supplement the support that we get from significant others in interpersonal relationships. Some groups, like therapy groups for survivors of sexual attack or back up groups for people with cancer, exist primarily to provide emotional support. While these groups may also run across instrumental needs through connections and referrals to resource, they fulfill the interpersonal need for belonging that is a central human being need.

Groups Run into Identity Needs

Our affiliations are building blocks for our identities, because grouping membership allows us to apply reference groups for social comparison—in short, identifying united states of america with some groups and characteristics and separating us from others. Some people bring together groups to exist affiliated with people who share similar or desirable characteristics in terms of beliefs, attitudes, values, or cultural identities. For case, people may join the National System for Women because they want to affiliate with others who support women'due south rights or a local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) because they want to chapter with African Americans, people concerned with ceremonious rights, or a combination of the two. Grouping memberships vary in terms of how much they bear upon our identity, as some are more prominent than others at various times in our lives. While religious groups equally a whole are too large to exist considered minor groups, the work that people do every bit a office of a religious customs—as a lay leader, deacon, member of a prayer group, or committee—may have deep ties to a person's identity.

Group membership helps run across our interpersonal needs by providing an opportunity for affection and inclusion.

The prestige of a group can initially concenter u.s.a. because we desire that group's identity to "rub off" on our own identity. Likewise, the achievements we make every bit a group member can enhance our self-esteem, add together to our reputation, and allow us to create or project certain identity characteristics to appoint in impression management. For instance, a person may take numerous tests to get a office of Mensa, which is an arrangement for people with high IQs, for no material gain but for the recognition or sense of achievement that the affiliation may bring. Likewise, people may join sports teams, professional organizations, and honor societies for the sense of achievement and affiliation. Such groups let u.s. opportunities to better ourselves by encouraging further development of skills or knowledge. For example, a person who used to play the oboe in high school may join the community band to continue to amend on his or her ability.

Types of Small Groups

At that place are many types of small groups, merely the most common stardom made betwixt types of pocket-size groups is that of task-oriented and relational-oriented groups (Hargie, 2011). Chore-oriented groups are formed to solve a trouble, promote a cause, or generate ideas or information (McKay, Davis, & Fanning, 1995). In such groups, like a committee or report group, interactions and decisions are primarily evaluated based on the quality of the final production or output. The three chief types of tasks are production, discussion, and problem-solving tasks (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). Groups faced with production tasks are asked to produce something tangible from their grouping interactions such equally a study, design for a playground, musical performance, or fundraiser outcome. Groups faced with discussion tasks are asked to talk through something without trying to come up upwardly with a right or wrong answer. Examples of this type of group include a back up group for people with HIV/AIDS, a book lodge, or a grouping for new fathers. Groups faced with problem-solving tasks have to devise a course of action to meet a specific demand. These groups also normally include a production and discussion component, but the end goal isn't necessarily a tangible product or a shared social reality through discussion. Instead, the end goal is a well-thought-out idea. Chore-oriented groups require honed problem-solving skills to accomplish goals, and the structure of these groups is more rigid than that of relational-oriented groups.

Relational-oriented groups are formed to promote interpersonal connections and are more focused on quality interactions that contribute to the well-existence of group members. Conclusion making is directed at strengthening or repairing relationships rather than completing discrete tasks or debating specific ideas or courses of action. All groups include task and relational elements, so it'due south best to think of these orientations as two ends of a continuum rather than equally mutually exclusive. For case, although a family unit works together daily to accomplish tasks like getting the kids ready for school and friendship groups may programme a surprise political party for ane of the members, their primary and most meaningful interactions are still relational. Since other chapters in this book focus specifically on interpersonal relationships, this affiliate focuses more than on task-oriented groups and the dynamics that operate within these groups.

To more specifically expect at the types of small groups that exist, we can examine why groups form. Some groups are formed based on interpersonal relationships. Our family and friends are considered primary groups, or long-lasting groups that are formed based on relationships and include significant others. These are the pocket-sized groups in which nosotros interact most frequently. They form the basis of our society and our private social realities. Kinship networks provide important support early on in life and see physiological and safe needs, which are essential for survival. They as well encounter higher-lodge needs such equally social and cocky-esteem needs. When people do not interact with their biological family, whether voluntarily or involuntarily, they tin establish fictive kinship networks, which are composed of people who are not biologically related only fulfill family unit roles and help provide the same support.

We besides interact in many secondary groups, which are characterized by less frequent face-to-face interactions, less emotional and relational communication, and more task-related advice than chief groups (Barker, 1991). While nosotros are more likely to participate in secondary groups based on cocky-interest, our primary-group interactions are often more reciprocal or other oriented. For example, nosotros may bring together groups considering of a shared interest or need.

Groups formed based on shared interest include social groups and leisure groups such as a group of independent film buffs, science fiction fans, or bird watchers. Some groups form to run into the needs of individuals or of a detail group of people. Examples of groups that meet the needs of individuals include written report groups or support groups similar a weight loss group. These groups are focused on individual needs, even though they meet as a group, and they are also often discussion oriented. Service groups, on the other hand, work to meet the needs of individuals but are task oriented. Service groups include Habitat for Humanity and Rotary Lodge capacity, amid others. Still other groups class around a shared demand, and their principal task is advancement. For instance, the Gay Men's Health Crisis is a group that was formed by a pocket-size grouping of eight people in the early on 1980s to advocate for resources and support for the notwithstanding relatively unknown affliction that would later be known as AIDS. Similar groups form to advocate for everything from a stop sign at a neighborhood intersection to the end of human being trafficking.

As we already learned, other groups are formed primarily to reach a job. Teams are task-oriented groups in which members are especially loyal and dedicated to the chore and other group members (Larson & LaFasto, 1989). In professional and civic contexts, the word squad has become popularized as a means of drawing on the positive connotations of the term—connotations such as "high-spirited," "cooperative," and "hardworking." Scholars who have spent years studying highly effective teams have identified several common factors related to their success. Successful teams accept (Adler & Elmhorst, 2005)

- clear and inspiring shared goals,

- a results-driven structure,

- competent squad members,

- a collaborative climate,

- high standards for performance,

- external support and recognition, and

- ethical and accountable leadership.

Increasingly, pocket-sized groups and teams are engaging in more virtual interaction. Virtual groups take advantage of new technologies and encounter exclusively or primarily online to accomplish their purpose or goal. Some virtual groups may complete their task without ever existence physically face-to-face. Virtual groups bring with them distinct advantages and disadvantages that you can read more than about in the "Getting Plugged In" feature side by side.

"Getting Plugged In"

Virtual Groups

Virtual groups are at present common in academic, professional, and personal contexts, as classes meet entirely online, piece of work teams interface using webinar or video-conferencing programs, and people connect effectually shared interests in a diverseness of online settings. Virtual groups are popular in professional contexts because they can bring together people who are geographically dispersed (Ahuja & Galvin, 2003). Virtual groups also increase the possibility for the inclusion of diverse members. The power to transcend distance means that people with diverse backgrounds and diverse perspectives are more than hands accessed than in many offline groups.

I disadvantage of virtual groups stems from the difficulties that technological mediation presents for the relational and social dimensions of group interactions (Walther & Bunz, 2005). Every bit we will learn afterwards in this affiliate, an important part of coming together as a group is the socialization of group members into the desired norms of the grouping. Since norms are implicit, much of this data is learned through observation or conveyed informally from ane grouping member to another. In fact, in traditional groups, group members passively acquire 50 pct or more of their knowledge about grouping norms and procedures, meaning they discover rather than directly ask (Comer, 1991). Virtual groups experience more than difficulty with this part of socialization than copresent traditional groups do, since any form of electronic arbitration takes abroad some of the richness present in face up-to-face interaction.

To help overcome these challenges, members of virtual groups should be prepared to put more time and endeavor into building the relational dimensions of their group. Members of virtual groups need to make the social cues that guide new members' socialization more explicit than they would in an offline group (Ahuja & Galvin, 2003). Grouping members should as well contribute frequently, fifty-fifty if simply supporting someone else's contribution, because increased participation has been shown to increase liking among members of virtual groups (Walther & Bunz, 2005). Virtual group members should also make an effort to put relational content that might otherwise exist conveyed through nonverbal or contextual means into the verbal role of a message, equally members who include little social content in their messages or only communicate near the group's task are more negatively evaluated. Virtual groups who do not overcome these challenges volition probable struggle to encounter deadlines, interact less frequently, and experience more than absenteeism. What follows are some guidelines to help optimize virtual groups (Walter & Bunz, 2005):

- Become started interacting equally a group as early as possible, since information technology takes longer to build social cohesion.

- Interact frequently to stay on task and avoid having work build upwardly.

- Start working toward completing the task while initial communication almost setup, organization, and procedures are taking place.

- Respond overtly to other people's letters and contributions.

- Be explicit about your reactions and thoughts since typical nonverbal expressions may non be received as hands in virtual groups as they would be in colocated groups.

- Set deadlines and stick to them.

- Make a list of some virtual groups to which you currently vest or have belonged to in the past. What are some differences between your experiences in virtual groups versus traditional colocated groups?

- What are some group tasks or purposes that you recollect lend themselves to being accomplished in a virtual setting? What are some group tasks or purposes that you think would be all-time handled in a traditional colocated setting? Explain your answers for each.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Small Groups

As with anything, minor groups have their advantages and disadvantages. Advantages of pocket-sized groups include shared conclusion making, shared resources, synergy, and exposure to diversity. It is within small groups that most of the decisions that guide our country, introduce local laws, and influence our family interactions are made. In a autonomous society, participation in conclusion making is a key part of citizenship. Groups also help in making decisions involving judgment calls that have upstanding implications or the potential to negatively touch people. Individuals making such high-stakes decisions in a vacuum could have negative consequences given the lack of feedback, input, questioning, and proposals for alternatives that would come from group interaction. Group members as well aid aggrandize our social networks, which provide access to more than resources. A local customs-theater grouping may be able to put on a production with a limited budget by cartoon on these connections to become set-building supplies, props, costumes, actors, and publicity in ways that an private could not. The increased knowledge, various perspectives, and admission to resources that groups possess relates to another advantage of pocket-size groups—synergy.

Synergy refers to the potential for gains in performance or heightened quality of interactions when complementary members or member characteristics are added to existing ones (Larson Jr., 2010). Because of synergy, the final grouping product can be ameliorate than what any individual could take produced alone. When I worked in housing and residence life, I helped coordinate a "World Cup Soccer Tournament" for the international students that lived in my residence hall. As a grouping, we created teams representing different countries effectually the world, made brackets for people to track progress and predict winners, got sponsors, gathered prizes, and ended up with a very successful event that would not have been possible without the synergy created past our collective group membership. The members of this group were also exposed to international diversity that enriched our experiences, which is too an advantage of group advice.

Participating in groups tin can also increment our exposure to variety and broaden our perspectives. Although groups vary in the multifariousness of their members, we can strategically choose groups that expand our diversity, or we can unintentionally terminate up in a diverse group. When we participate in small groups, we expand our social networks, which increase the possibility to interact with people who take different cultural identities than ourselves. Since grouping members work together toward a mutual goal, shared identification with the task or group tin can give people with diverse backgrounds a sense of commonality that they might not take otherwise. Even when grouping members share cultural identities, the diversity of experience and opinion within a group can lead to broadened perspectives as culling ideas are presented and opinions are challenged and defended. One of my favorite parts of facilitating class word is when students with different identities and/or perspectives teach one another things in ways that I could non on my own. This example brings together the potential of synergy and variety. People who are more introverted or simply avoid group advice and voluntarily distance themselves from groups—or are rejected from groups—risk losing opportunities to learn more about others and themselves.

A social loafer is a dreaded group member who doesn't practise his or her share of the work, expecting that others on the group won't notice or volition choice up the slack.

There are also disadvantages to small group interaction. In some cases, one person tin can be just as or more constructive than a grouping of people. Think virtually a state of affairs in which a highly specialized skill or knowledge is needed to get something washed. In this situation, one very knowledgeable person is probably a amend fit for the task than a group of less knowledgeable people. Group interaction also has a trend to tiresome down the controlling process. Individuals continued through a hierarchy or chain of command often work ameliorate in situations where decisions must be made under fourth dimension constraints. When grouping interaction does occur nether time constraints, having i "point person" or leader who coordinates action and gives final approval or disapproval on ideas or suggestions for deportment is best.

Grouping communication also presents interpersonal challenges. A mutual problem is coordinating and planning group meetings due to decorated and conflicting schedules. Some people too have difficulty with the other-centeredness and cocky-cede that some groups require. The interdependence of group members that we discussed earlier can also create some disadvantages. Grouping members may take advantage of the anonymity of a group and appoint in social loafing, pregnant they contribute less to the grouping than other members or than they would if working alone (Karau & Williams, 1993). Social loafers expect that no one will find their behaviors or that others will pick upwards their slack. It is this potential for social loafing that makes many students and professionals dread grouping work, especially those who have a tendency to cover for other grouping members to prevent the social loafer from diminishing the group'southward productivity or output.

"Getting Competent"

Improving Your Group Experiences

Like many of you, I also had some negative grouping experiences in college that made me think similarly to a educatee who posted the following on a teaching weblog: "Group work is code for 'work as a group for a form less than what you tin get if you work alone'" (Weimer, 2008). But so I took a class called "Pocket-sized Group and Squad Advice" with an amazing teacher who afterwards became ane of my most influential mentors. She emphasized the fact that nosotros all needed to increase our cognition about grouping communication and group dynamics in social club to meliorate our group communication experiences—and she was correct. So the first slice of advice to help yous starting time improving your group experiences is to closely study the group communication chapters in this textbook and to apply what you learn to your group interactions. Neither students nor kinesthesia are born knowing how to role as a grouping, still students and faculty often recollect we're supposed to learn as nosotros get, which increases the likelihood of a negative experience.

A second piece of advice is to meet frequently with your group (Myers & Goodboy, 2005). Of course, to do this you lot accept to overcome some scheduling and coordination difficulties, only putting other things aside to work as a group helps set up a norm that group work is important and worthwhile. Regular meetings as well allow members to interact with each other, which tin can increase social bonds, build a sense of interdependence that can help diminish social loafing, and establish other important rules and norms that will guide futurity group interaction. Instead of committing to frequent meetings, many educatee groups use their first meeting to equally divide upwardly the group's tasks and then they can then go off and work solitary (not as a group). While some group work can definitely be washed independently, dividing up the piece of work and assigning someone to put it all together doesn't let group members to take reward of one of the most powerful advantages of group work—synergy.

Last, establish group expectations and follow through with them. I recommend that my students come up upwards with a group proper noun and create a contract of grouping guidelines during their first meeting (both of which I learned from my group advice teacher whom I referenced earlier). The grouping name helps begin to establish a shared identity, which then contributes to interdependence and improves performance. The contract of group guidelines helps make explicit the group norms that might have otherwise been left implicit. Each group member contributes to the contract and and then they all sign it. Groups often make guidelines about how meetings volition be run, what to do nigh lateness and attendance, the type of climate they'd like for word, and other relevant expectations. If group members finish upwards falling brusque of these expectations, the other group members can remind the straying fellow member of the contact and the fact that he or she signed it. If the group encounters further issues, they can use the contract as a footing for evaluating the other group fellow member or for communicating with the instructor.

- Practice yous agree with the student'southward quote about group work that was included at the first? Why or why not?

- The second recommendation is to meet more with your grouping. Acknowledging that schedules are hard to coordinate and that that is not really going to modify, what are some strategies that you lot could utilise to overcome that challenge in order to get time together every bit a group?

- What are some guidelines that you retrieve you lot'd like to include in your contract with a future group?

Fundamental Takeaways

- Getting integrated: Small group communication refers to interactions among iii or more people who are connected through a common purpose, common influence, and a shared identity. Small groups are important communication units in bookish, professional person, borough, and personal contexts.

-

Several characteristics influence small groups, including size, structure, interdependence, and shared identity.

- In terms of size, small groups must consist of at to the lowest degree three people, simply at that place is no set up upper limit on the number of group members. The platonic number of group members is the smallest number needed to competently complete the group's task or reach the group'south purpose.

- Internal influences such as member characteristics and external factors such as the group's size, task, and access to resource impact a group's structure. A grouping'due south structure also affects how grouping members communicate, as some structures are more centralized and hierarchical and other structures are more decentralized and equal.

- Groups are interdependent in that they have a shared purpose and a shared fate, meaning that each group fellow member'south actions affect every other group member.

- Groups develop a shared identity based on their task or purpose, previous accomplishments, future goals, and an identity that sets their members apart from other groups.

-

Small groups serve several functions as they encounter instrumental, interpersonal, and identity needs.

- Groups meet instrumental needs, as they allow us to pool resources and provide access to data to better assistance usa survive and succeed.

- Groups meet interpersonal needs, equally they provide a sense of belonging (inclusion), an opportunity to participate in decision making and influence others (control), and emotional support.

- Groups meet identity needs, as they offer usa a chance to affiliate ourselves with others whom we perceive to be like us or whom we admire and would like to be associated with.

-

At that place are various types of groups, including job-oriented, relational-oriented, primary, and secondary groups, also as teams.

- Task-oriented groups are formed to solve a trouble, promote a crusade, or generate ideas or information, while relational-oriented groups are formed to promote interpersonal connections. While there are elements of both in every group, the overall purpose of a group tin can commonly be categorized as primarily chore or relational oriented.

- Primary groups are long-lasting groups that are formed based on interpersonal relationships and include family and friendship groups, and secondary groups are characterized by less frequent interaction and less emotional and relational communication than in primary groups. Our communication in chief groups is more frequently other oriented than our communication in secondary groups, which is often self-oriented.

- Teams are similar to task-oriented groups, but they are characterized by a high degree of loyalty and dedication to the group's task and to other group members.

- Advantages of group communication include shared decision making, shared resources, synergy, and exposure to diversity. Disadvantages of group communication include unnecessary group formation (when the task would be better performed past one person), difficulty coordinating schedules, and difficulty with accountability and social loafing.

Exercises

- Getting integrated: For each of the follow examples of a small-scale group context, indicate what y'all think would be the ideal size of the grouping and why. Also indicate who the ideal group members would be (in terms of their occupation/major, role, level of expertise, or other characteristics) and what structure would work best.

- A report group for this class

- A commission to decide on library renovation plans

- An upper-level college course in your major

- A group to advocate for more sensation of and back up for abandoned animals

- List some groups to which y'all have belonged that focused primarily on tasks and then list some that focused primarily on relationships. Compare and dissimilarity your experiences in these groups.

- Synergy is one of the primary advantages of pocket-size group communication. Explain a time when a group you were in benefited from or failed to achieve synergy. What contributed to your success/failure?

References

Adler, R. B., and Jeanne Marquardt Elmhorst, Communicating at Work: Principles and Practices for Businesses and the Professions, 8th ed. (Boston, MA: McGraw-Colina, 2005), 248–l.

Ahuja, Thousand. 1000., and John E. Galvin, "Socialization in Virtual Groups," Journal of Management 29, no. 2 (2003): 163.

Barker, D. B., "The Behavioral Analysis of Interpersonal Intimacy in Grouping Development," Pocket-size Grouping Research 22, no. 1 (1991): 79.

Comer, D. R., "Organizational Newcomers' Conquering of Information from Peers," Management Advice Quarterly v, no. 1 (1991): 64–89.

Ellis, D. Thou., and B. Aubrey Fisher, Small Group Conclusion Making: Communication and the Group Process, 4th ed. (New York: McGraw-Colina, 1994), 57.

Girl Scouts, "Facts," accessed July xv, 2012, http://world wide web.girlscouts.org/who_we_are/facts.

Hargie, O., Skilled Interpersonal Interaction: Research, Theory, and Do, 5th ed. (London: Routledge, 2011), 452–53.

Karau, S. J., and Kipling D. Williams, "Social Loafing: A Meta-Analytic Review and Theoretical Integration," Periodical of Personality and Social Psychology 65, no. four (1993): 681.

Larson, C. Due east., and Frank M. J. LaFasto, TeamWork: What Must Go Right/What Must Go Incorrect (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1989), 73.

Larson Jr., J. R., In Search of Synergy in Small Group Performance (New York: Psychology Press, 2010).

McKay, Grand., Martha Davis, and Patrick Fanning, Letters: Advice Skills Book, 2nd ed. (Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, 1995), 254.

Myers, S. A., and Alan Thou. Goodboy, "A Study of Grouphate in a Course on Modest Group Advice," Psychological Reports 97, no. 2 (2005): 385.

Walther, J. B., and Ulla Bunz, "The Rules of Virtual Groups: Trust, Liking, and Operation in Computer-Mediated Advice," Periodical of Advice 55, no. 4 (2005): 830.

Weimer, Thou., "Why Students Hate Groups," The Pedagogy Professor, July one, 2008, accessed July xv, 2012, http://world wide web.teachingprofessor.com/manufactures/instruction-and-learning/why-students-detest-groups.

Source: https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication/chapter/13-1-understanding-small-groups/

0 Response to "what appear to be the characteristics of effective teams in public health settings?"

Post a Comment